|

Reading

Augustine

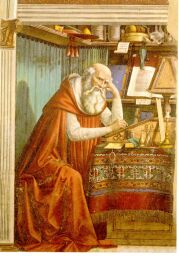

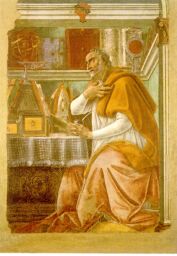

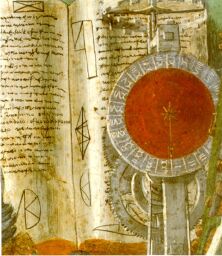

St. Jerome, quill in hand, offers attentive readers an approach to conversion. He would share the fruits of his meditations, enlarging the company of believers. His study incorporates the tools of studious work, calling attention to the circumstances in which he works, inviting his readers to appreciate and share his resources as well as his vision. We might begin with the open page of his book, neatly clipped to its stand, inviting our attention. Spectacles and scissors, neatly stored, await use, the very tools a merchant familiar with cloth would recognize as instrumental in the creation and inspection of rare fabrics, including the oriental carpet underlying Jerome’s work. Attention perhaps radiates from Jerome’s steady expression and gesture to the finest sensations attending each tool of scholarship, every fold of cloth. Every component of Jerome’s work-space invites attention. Each is available for our use, and sharing his activities, we may better appreciate the fruits of his labors. Like the accumulation of material detail in his study, the accumulation of insights from his writings may deepen our understanding of scripture St. Augustine, hand to heart, pauses in his studies, deep in thought. He, too, appears surrounded by aids to meditation. Unlike Jerome’s vision, however, Augustine’s offers no awareness of onlookers. We must explore the circumstances in which his vision arises. The ink-jar and pen he holds, and the open book suggest reading and responsive writing. Augustine’s book, perhaps scripture, is not available for our reading, and the bishop’s mitre invites less attention than the shelf above, with distinct, elevated objects sharing the level of Augustine’s vision. Before Augustine a metal band, conspicuously askew to the geometrical regularity of central earth and parallel tropics, marks the ecliptic, indicating seasonally varying heights for sunlight. Behind appears a readable book, whose geometrical diagrams reappear in a moving clock. Augustine’s informing text is unavailable to us, but the opened pages of a geometry text delineate geometrical relations which are actualized in the moving circles of his clock. Before telling time, we may decipher in a recorded conversation:

Where is brother Mariano?

Such lapses of attention, no doubt occurring in Augustine’s time, occur again in Botticelli’s Florence, not least among the Ognissanti brethren, whether brothers of the cloth, or visitors to the Ognissanti church. As readers, the details of Boticelli’s text return us to our attempt to see through Augustine’s eyes. Like the departed monks, we fail to follow Augustine’s example. An aid, however, does appear in the shelf of instruments at eye level. An armillary sphere shows the earth surrounded by bands, Askew from the regular equator, the ecliptic calls attention to the shifting times of daylight and darkness. Through the opened text which the Ognissanti brothers have left unexamined, we come to a second pointer, Augustine’s clock. This marvel of geometric form, now animated with motion, invites particular attention to day and time.

Toothed wheels, turned

by a falling weight,

Whatever the artificial illumination of Augustine’s study, whether in Hippo, in the Ognissanti setting of Botticelli’s recollection, or in a present viewer’s study, on one particular day, as Augustine has elsewhere recorded, a potential conversion actualized in time.

St. Augustine was sitting in his cell one day

Jerome’s disappearance from the vision of his companions marked his death, but for those like Augustine, with eyes to see, Jerome approaching heaven experiences the very illumination Augustine seeks in meditation. Jerome, as speaker, Jerome as trusted guide, reinforces Augustine’s resolve. On the one hand, Augustine can appreciate his own moment of illumination. On the other hand, he has hardly emerged from darkness. What his vision offers is not the promised land: his vision reinforces his bond with Jerome, his heightened recognition of love as the bond which will lead him, in Jerome’s company, to the promised land. Ghirlandaio’s Jerome offers the accumulation of experience which an attentive reader can also develop through the labour of ongoing meditation, of disciplined study. We may pass beyond the vanities of worldly concerns through such activity. His painting, however, in the richness of sensation offered by paint, calls attention to the very attractions which Augustine would pass beyond. In seeking a way through the world, Ghirlandaio’s saint returns us to it. Boticelli’s Augustine offers a worldly vision, not of paradise, but of loving friendship, of good company in crucial times. More important than the meditative insights he will continue to pursue, is his trust in the friendship of Jerome, whose real presence will lead him toward his own passing beyond the light of this world into that of paradise. Augustine’s Confessions offer the company of a sinner to invite his readers to particularize their own experiences, and hence to realize their own conversion. Conversion depends on psychology, not on ritual or doctrine. Out with companions under cover of darkness, Augustine steals a pear. Years later he returns again and again to ponder why. Not to satisfy hunger. Not to discover a finer taste. Only to break the law, to become the one who sets law, not the one who practices law. His community, however, all would-be individuals above the law, can act only in company, a company with the pretense of individual power. To appreciate a new direction, Augustine must experience the self-deceptions actually working in particular moments. The evidence of experiences to be shunned, as of those to be sought, is not in doctrine, but in actual experiences. Efficacious confession requires the discovery of deception, not the blind adherence to a presumed code. Boticcelli’s testimony is less the rise to perfect vision, more the heightening of attention to loving friendship, to real community. The Ognissanti brotherhood, presumably organized to guide illumination, with rules and restrictions, fails to develop the personal experience Boticcelli sees in Augustine’s test of friendship, and passes on to attentive company. Botticelli shared with Savanarola a distrust of Florentine sensibilities. His Augustine looks back to the individual voices of Dante he illustrated. Ironically, the bonfire of the vanities which consumed, among many and varied pictures some of Botticelli’s, led not to a purified Florentine community, but to the funeral pyre of the would-be reformer. Girolamo Savonarola appears through Fra Bartolomeo’s vision as a lone visionary in a dark world, beyond friendship, beyond community, Augustine, seeking perfection, discovers his orientation through the presence of his friend, Jerome. Savanarola, the isolated visionary, appears in Fra Bartolomeo’s portrait as Augustine’s antithesis.

Botticelli’s relationship to Augustine parallels Augustine’s relationship to Jerome. The voice of Augustine, centuries after his death, no doubt inspired Botticelli. Augustine’s voice still speaks to those seeking good company, not least through his Confessions:

|