|

Weeping Woman

Funeral

urns marked the graves of notable warriors like Agamemnon. Mourners could

offer wine to a departed shade, wine passing through soil to refresh a

distinctive voice which, for a moment, can engage the suppliant.

Foreseeing

the death of her husband, the Trojan prince Hector, Andromache rushes to

the walls to stop his exit from Troy back into battle, to stop him from

confrontation with the Greek, Achilles, to stay his fate. Hector

understands, however, that Andromache’s love depends precisely on his

willingness to face Achilles, to confront his fate, to attempt the defense

of her, their child, and Troy, all the more telling for its eventual

failure.

Here

lies Timokritos: soldier: valiant in battle.

Ares spares not the brave man, but the coward.

– Anakreon, The Greek Anthology

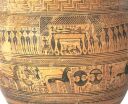

Death

in battle, of course, offers fame. Our funeral urn depicts a fallen

warrior, with shroud lifted, dogs below, wife and child at feet, and women

mourners tearing hair in timeless gestures of grief. Below the bier, a

procession of warriors recall the conditions and activities meriting fame.

Their warrior will enter the land of shades, where only memories of his

deeds in life can momentarily restore his features and actions. The more

particular the recollections, the more that shade will, for a time, come

back to life. Greek stories, including the Iliad, take place in the

theatre of the mind. Those who carried offerings of wine would pour their

offering through the urn, open at the bottom. Seeping into the soil, down

to the shades below, the wine might raise from the shadowy dead, the sound

of their warrior’s voice. The Iliad, recited aloud, recalls the voices

as well as the activities of the glorious dead.

Wife

and child appear at the feet of their fallen lord. Consider Hector’s

telling prediction of their fate: public death with disgrace to Astyonax,

“Lord of the City,” a potential magnet for dissident captives not to be

saved through sentimentality. Bondage to a noble killer of Trojan royalty

for his wife, Andromache. The distance between notions of justice, of divine love,

and the stages of grief common to monotheistic religions including

Christianity, are less than

apparent in this scene. Considering, among other scenes, widows of

fallen soldiers, perhaps from the Spanish civil war as well as the Trojan

War, Wallace Stevens calls attention to the powers of imagination to

endure, not through transcendence of the ego, but in accordance with harsh

fate:

Wallace

Stevens

Another

Weeping Woman

Pour the

unhappiness out

From your too bitter heart,

Which grieving will not sweeten.

Poison

grows in this dark.

It is in the water of tears

Its black blooms rise.

The

magnificent cause of being,

The imagination, the one reality

In this imagined world

Leaves

you

With him for whom no phantasy moves,

And you are pierced by a death.

Picasso's

Weeping Women

|