|

Reading Mary

of Burgundy

Mary of Burgundy Reads Mary of Burgundy appears immersed in a particular hour in 1477, realizing in the theatre of her mind the presence of Mary. Her intercessor, incarnate in imagination, offers solace. Mary’s father, Charles the Bold, has died, leaving her at twenty the Duchess of Burgundy. Louis XI of France threatening her inheritance, offers the reconciliation of marriage, but she will prefer Maximilian of Austria, the future Holy Roman Emperor (1493). Her reading begins with a flourished O, perhaps the beginning of a poem she would particularly cherish at this pressing moment: Obsecro te (I beseech thee) –

Mary’s reading, a

spiritual exercise, depends for effect on her active participation

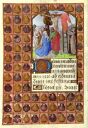

Thomas Becket Approaches Mary Her prayer follows the inspiration of a predecessor, Thomas Becket, also actualizing a particular moment. Becket, as chancellor of England (1155–62), had furthered the policies of Henry II of England. But as archbishop of Canterbury (1162–70) he acted independently, refusing to cede church prerogatives to the monarch. A devote of Mary, he composed the Obsecro te that now inspires Mary. A flourished capital recalls in black the death Becket will face with Mary’s support, as well as the death of Mary’s father, Charles the Bold. Thomas Becket turns from his former king to Mary, the object of his present and enduring veneration. Surely Mary of Burgundy, herself oppressed with suitors, enjoys the power of Mary to supplant Henry as the object of Becket’s devotion.

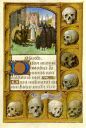

Mary’s Nature and Revelation Mary may revive spirits through springtime flowers. Variety appears not just in diversity of shapes, colors, sizes, but also in every individual of a common species. The least flower, the tiniest of moths, all of creation, lives with distinction. Mary recognizes also in the shortening days of autumn the character of death, the passage of all mortals. Each skull she notes, carries the distinctive impressions of individual experience.

Mary no doubt

appreciates in scallop shells the situations of souls seeking

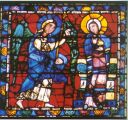

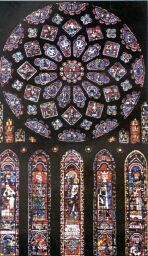

Mary Builds Chartres Mary's blue robe, a relic brought to Chartres in France by crusaders returning from Jerusalem, mirrors the celestial blue sky surrounding her in heaven. Sunlight radiates from each. Suppliants before her robe, like suppliants looking up to the blue cloak of heavens, seek her presence, her light. Miracles follow.

When fire destroyed

her Romanesque church in 1194, stone crumbled, metal melted, but her

robe survived intact. Her message: build a suitable home. The present Chartres Cathedral, consecrated in 1260, established the structures and

energies which would populate Europe with Notre Dames, unprecedented

communal centers,

Wide participation

in the construction brought together communities,

Within one-hundred years Notre Dame spreads through the power of Mary gothic structures and gothic practices throughout Europe.

Mary Brings Light Those seeking Mary’s intercession at Chartres literally stand in heavenly light. Every hour of every day varies Mary’s presence: circumstances ─ weather, politics, economics, moods ─ shift and flow. Life generating sunlight, infinitely inflected with Mary‘s intercessions, move each and every suppliant. At vespers (evening), approaching the Western portal, the setting sun animates the judgment day arching the doorway, anticipating two approaching worlds, the illuminations of heaven, the shadings of hell. Within, eastward, altar candles anticipate morning sunrise. At transept, northern exposure offsets temperate South rose, realizing under the protective wall the temperate garden which shelters all creatures. What drives such activity? Not, presumably, the technical discovery of vaulting, flying buttresses, illuminated glass. More, the spirit of Mary, a new influence manifesting new circumstances and desires throughout Europe in the 12th century.

The Art of Courtly Love In 1137, Eleanor succeeded her father William X, as ruler of Aquitane, and married (by prearrangement of her father) Louis VII of France. She joined Louis on the second crusade, and exercised considerable influence in arts as well as politics at Champagne. At Poitiers, she established courtly life and manners praised by troubadours of the time. Her daughter Marie, Countess of Champagne, inspired The Art of Courtly Love (Liber de arte honeste amandi et reprobatione inhonesti amoris), written about 1185 by her chaplain André. Divorced from Louis in 1152, she married Henry Plantagenet, 12 years her junior. Her children by both marriages came to occupy a significant portion of European thrones. Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde assumes the conventions and psychology implicit in the art of courtly love.

|