|

III Illuminating Love

Chaucer: Troilus and

Criseyde

Medieval Lyrics

Innocent III: On Misery

Saint Augustine:

Confessions

Capellanus: The Art of

Courtly Love

Augustine's Fruit

Chaucer:

Troilus and Criseyde (original)

Engaging Chaucer

Our subject has one focus: the course of love.

What makes love compelling?

After reading, pick one passage that shows

how lovers act at a particular time and place,

in a particular stage of their encounters.

Chaucer’s essential

focus is on what contributes

to the joy Troilus and Criseyde anticipate and

eventually enjoy. Attentive readers will work to see

through their eyes, their senses, their assumptions

and expectations, their desires.

This is no little

thing for me to say;

It stuns imagination to express.

For each began to honour and obey

The other’s pleasure; happiness, I guess,

So praised by learned men, is something less.

This joy may not be written down in ink,

For it surpasses all that heart can think.

(III,242, p 171)

After appreciating the

fruits of love you may of course

consider the costs. Pandar, as well as Criseyede and Troilus, are initially wary of love.

And Love’s old sweet song ends unhappily, as court ladies daily hear

from fashionable singers. None-the-less all three at times agree

with Chaucer’s condemnation of nay-sayers.

Lord! Do you think

some avaricious ape

Who girds at love and scorns it as a toy,

Out of the pence that he can hoard and scrape,

Had ever such a moment of pure joy

As love can give, pursuing his foul ploy?

Never believe it! For, by God above,

No miser ever knew the joy of love.

(III, 195, p 159)

Misers would answer

‘Yes,’; but, Lord, they’re liars!

Busy and apprehensive, old and cold

And sad, who think of love as crazed desires;

But it shall happen to them as I told;

They shall forgo their silver and their gold

And live in grief; God grant they don’t recover,

And God advance the truth of every lover!

(III, 196, p 159)

I wish to God those

wretches that dismiss

Love and its service sprouted ears as long

As Midas did, that man of avarice;

Would they were given drink as hot and strong

As Crassus swallowed, being in the wrong,

To teach such folk that avarice is vicious

And love is virtue, which they think pernicious.

(III, 197, p 160)

Chaucer’s World

After

centuries of patriarchal concerns with war and honor, medieval women

take center stage, and love flourishes in song (troubadours), in verse

and prose

(The Divine Comedy and The Decameron

as well as Troilus and Criseyde), in letters (Heloise and Abelard).

Consider Mary of Burgundy and the world she imagines thorough reading in

her book of Hours:

Reading Mary of

Burgundy

Consider six changes

from Greek culture which contribute to such new habits of attention.

A. Monotheistic belief

now assumes a creator who moves creatures through desire.

Among the most powerful of desires are sexual and familial love.

Love makes the world go ’round.

B. This world prepares

souls for life after death, for some in heaven, for some in hell.

The exercise of desire in this life establishes not just the direction

of life after death,

but more the development of character which will flourish or seethe in

heaven or in hell.

C. Since every soul is

unique, and the actions of every individual will lead

to heaven or to hell, the study of the psyche, psychology, takes

precedence.

Character no longer arises from the pursuit of excellence, from earned

pride.

Character takes shape from the company one keeps, from the practice of

love.

D. Pleasure and pain

are pointers to heaven and hell. To recollect

personal experiences of intense pleasure is to shape directions to

future bliss,

to salvation. To recollect personal experiences of pain is to shape

directions

away from future suffering, from damnation. Fearful isolation

characterizes damnation.

Cooperative company characterizes salvation.

E. Conversion,

re-orientation, changes not just what we see and do,

but how we see and act. Conversions may arise from the discovery of

generative patterns

in astronomy, in mathematics, in music (the medieval trivium).

Conversions may appear

in the discovery of a religious calling. But conversion most commonly

appears

when individuals fall in love.

E. Scripture directs

attention and focuses desire. The speaking soul anticipates,

discovers and actualizes the language of love. In the beginning was the

word . . .

Medieval Love

Lyrics

Chaucer identifies himself, not as a lover, but as a student of

love. He works to trace the sensations, the feelings and thoughts, the

language and actions of specific lovers as they unfold in specific

places at specific times. As an author, he stimulates us to

participation in the lover’s world, a necessary prerequisite if informed

judgments are to follow. Observation of actual experience, not just the

empty exercise of presuppositions, feeds recollection and recognition.

Consider the evidence of natural desire,

working just before dawn (at matins), equally apparent

in wildlife and in people

—

I have a gentil cock

I have a gentil cock,

Croweth me the day;

He doth me risen erly,

My matins for to say.

I have a gentil cock;

Comen he is of gret:

His comb is of red coral,

His tayil is of jet.

I have a gentil cock;

Comen he is of kynde;

His comb is of red coral,

His tayil is of Inde.

His legges been of

asor,

So gentil and so smale;

His spures arn of silver-whyt

Into the wortewale.

His eyen arn of

crystal,

Looking all in aumber;

And every nyght he percheth him

In myn lady’s chaumber.

The splendor of nature

appears through the rooster’s shape, coloration, gestures and voice. A

lover would himself perch in his lady’s chamber. Sexual passion

surely inspires this voice. The plumage, gestures,

voice and actions of birds draw attention to the

richness and energy of creation.

Consider now the

appearance of a mother at sunset.

Her shape, coloration, gestures and voice also demonstrate natural

passion. As the sun sets

(at vespers), as darkness grows, as chill spreads,

her memories pierce and fade —

Nu goth Sonne

Nu goth Sonne under

wode.

Me rueth, Mary, thy faire rode.

Nu goth Sonne under tree.

Me rueth, Mary, thy Sone and thee.

Now goes the sun below trees

I pity, Mary, thy faire face.

Now goes the sun (Son) under tree (cross).

I pity, Mary, thy son and thee.

Mary, of course,

recalls her son’s crucifixion. Her recollection, however, springs from

the natural events, so common but so potentially affecting, she senses

and inhabits. If spring and dawn evoke the promise of birth, of new

life, of beginnings, autumn recalls sufferings attending age,

experiences of mortality, endings. The observer, however, is not just

Mary, but also the speaker, who sorrows with Mary, not by understanding

her feelings, but by inhabiting her circumstances. Passion originates

with suffering (recall the Valentine convention, a heart pierced with

Cupid’s arrow), the heart contracts, and compassion with a fellow

sufferer follows.

Complementary

associations and desires arise

in the appearance of flourishing girl —

Stetit Puella

There stood the girl

In the crimson dress

At the softest press,

How that tunic rustled:

Eia!

There stood the girl,

Rosebud on a vine;

Face ashine,

Mouth a reddish bloom.

Eia!

Slender, lithe, dressed to impress, she invites, deserves and receives

attention. Appreciative observers, drawn by the blush animating her

mobile, expressive face, trace her attitudes, gestures, approaches,

anticipating closer acquaintance. Eyes may be windows of the soul,

widening, glistening when aroused in anticipation.

Here lips invite carnal knowledge, attracting through texture, through

gesture. Her lips invite not just

a momentary bliss, but further acquaintance with

the language of love.

Medieval observers

would recall a parallel scene,

the Stabat Mater, where Mary stood suffering as a lance pierced her

crucified son’s heart. Stetit Puella would replace such attentions with

current attractions.

But experiences of carnal passion and experiences

of familial compassion are related, facing pages

of common, essential experience.

Mary, of course, is an

exceptional, a matchless mother. Medieval approaches to her, however,

emphasize circumstances evident in many mothers. The recognition

of pregnancy engenders appropriate surprise. Mary’s exceptional

situation develops from the commonest

of the evidences of love: the desire of a mother for fruitful life, her

desire for her child’s happiness, her awareness

of inevitable pain —

I singe of a Maiden

I singe of a Maiden

That is makeless;

King of all kinges

To her Sone she ches.

He cam all so stille

Ther his Moder was,

As dew in Aperille

That falleth on the grass.

He cam all so stille

To his Modres bour,

As dew in Aperille

That falleth on the flour.

He cam all so stille

Ther his Moder lay,

As dew in Aperille

That falleth on the spray.

Moder and maiden

Was nevere non but she.

Well may swich a lady

Goddes Moder be.

This song assumes, of

course, listeners with shared religious beliefs. But the power of the

song grows

from the most natural of circumstances, the real appearance of dew

droplets, minute opalescent, omnipresent and illuminating nourishment.

Dew sustains equally the smallest blade of grass, the grandest oak,

the field mouse and the emperor. The archangel Gabriel appears to Mary,

announcing the conception of Christ.

But we may take equal energy not just from rituals including such as

baptism, but from the commonest

of sights available on any early spring morning.

Love makes the world go ’round.

Medieval Lyrics

Loves old sweet

song

Medieval troubadours

(perhaps in need of sustenance

in foreign lands) developed and practiced the language

of courtly love. Some might recall the joys of creation

in the accurate mimicking of springtime bird calls

(rou coucou for doves, cock-a-doodle-do for English roosters,

ri-ki-ki-ki for German roosters). Bird calls

might delight even more those who also recognized astonishingly complex

rhymes supporting such calls

as well as celestial and terrestrial geometries.

One song of courtly

love, In a garden under a hawthorn bower, demonstrates the appeal of

love to watchers,

well aware of love’s limits, but moved by apparent bliss. Aubades, dawn

songs, reappear in every age. If vespers, the time for evening

meditations, invite reconsideration

of daylight activities, dawn may serve as the time for renewed

engagements. But lovers prefer night.

Enclosed in a bower, out of sight and mind from public scrutiny, lovers

can escape the restrictions of judgment

to explore unconditional passion, to seek

their mutual bliss.

In a garden under a hawthorn bower

In a garden under a

hawthorn bower

A lover to his lady’s closely drawn

Until a watchman shouts the mourning hour.

O God! O God! how swift it comes—the dawn!

“Dear God, if this

night would never fail

And my lover never far from me was gone,

And the watchman never saw the morning pale

But, O my God! how swift it comes—the dawn!”

“Come, pretty boy,

give me a little kiss

Down in the meadow where birds sing endless song.

Forget my husband! Think—just think of this—

For, O my God! how swift it comes—the dawn!”

“Hurry, my boy. The

new games end at morn.

Down to that garden—those birds—that song!

Play, play till the crier blows his horn,

For, O my God! how swift it comes—the dawn!”

“Down in the sweet air

over the meadow hovering

I drank a sweet draught—long, so long—

Out of the air of my handsome, noble lover.

O God! O God! how swift it comes—the dawn!”

The lady’s pretty. She

has many charms.

Toward her beauty many men are drawn.

But she lies happy in one pair of arms.

O God! O God! how swift it comes—the dawn!

The lady, older and

more experienced than her lover, appreciates full well the disapproval

of outsiders,

of those who would curtail her passions. She directs

her younger lover at night to a bower where all blossoms, where birds

sing endless songs. In such a place

lovers freed from pressing duties may discover the bliss

of mutually engaging desires. As each seeks the other’s bliss, that

chain-reaction which fuels ecstasy unfolds, blossoms.

Her encouragement

contains, of course, the wisdom

of experience: “O God! O God! How swift it comes—

the dawn.” But she will seek out with her lover circumstances in which

such concerns will fade,

in which unconstrained desires may flourish. The experiences she seeks

and offers will not endure.

To attend to such limitations, however, will block

the experiences, however momentary, she senses

as living, experiences different in kind from

the reasonable calculations of duty.

The watchman, of

course, signals a return to reason

and civility. But those who hear this lady’s song,

even while sharing the watchman’s judgment,

may also cling for a moment to desire. Before

a possible resurrection, we may seek fulfillment

here and now:

This is no little

thing for me to say;

It stuns imagination to express.

For each began to honour and obey

The other’s pleasure; happiness, I guess,

So praised by learned men, is something less.

This joy may not be written down in ink,

For it surpasses all that heart can think.

(III,242, p 171)

Criseyde (and Troilus)

come to share the troubadour’s expressions of desire. The wisdom of

experience will find voice: “O God! O God! How swift it comes—the dawn.”

But Criseyde and Troilus will none-the-less seek out circumstances in

which such concerns fade, in which unconstrained desires flourish. Their

experiences,

love’s old sweet song, will not endure. Attending too early to such

limitations, however, blocks experience of love which offer the highest

sense of being alive. Later,

perhaps, we may return to the reasonable

calculations of duty.

Watchman, of course,

signal a return to reason and civility. But those who hear the

cautionary reassurance of civility, recalling then the song of love, may

cling for some moments to desire. Before a possible resurrection,

we may seek fulfillment here and now:

O God! O God! how

swift it comes—the dawn!

Mary Builds Chartres

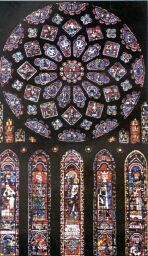

Mary's blue robe, a

relic brought to Chartres in France by crusaders returning from

Jerusalem, mirrors the celestial blue sky surrounding her in heaven.

Sunlight radiates from each. Suppliants before her robe, like

suppliants looking up to the blue cloak of heavens, seek her presence,

her light. Miracles follow.

When fire destroyed

her Romanesque church in 1194, stone crumbled, metal melted, but her

robe survived intact. Her message: build a suitable home. The present Chartres Cathedral, consecrated in 1260, established the structures and

energies which would populate Europe with Notre Dames, unprecedented

communal centers,

all arising within a few score years. Pointed, ribbed vaulting

buttressed outside enabled vertical heights unimagined previously, with

openings for light-radiating rose windows, with lancet windows opening

out lancet walls, illuminating

Mary’s virtues.

Wide participation

in the construction brought together communities,

kings and commoners, men and women, elders and youth. Stories abound.

Kings and commoners side-by-side pull stone-carts to rising walls.

Ben Shahn invites continuing participation —

. . . an

itinerant wanderer traveling over country roads in thirteenth-century

France who comes across a man exhaustedly pushing a wheelbarrow full

of rubble. He asks what the man is doing. ‘God only knows. I push

these damn stones around from sunup to sundown, and in return, they

pay me barely enough to keep a roof over my head.’

“Farther down the

road, the traveler meets another man, just as exhausted, pushing

another filled barrow. In reply to the same question, the second man

says, ‘I was out of work for a long time. My wife and children were

starving. Now I have this. It’s killing, but I’m grateful for it all

the same.”

“Just before

nightfall, the traveler meets a third exploited stone-hauler. When

asked what he is doing, the fellow replies, ‘I’m building Chartres

Cathedral.’”

Within one-hundred

years Notre Dame spreads through the power of Mary gothic structures and

gothic practices throughout Europe.

Mary Brings Light

Those seeking Mary’s

intercession at Chartres literally stand in heavenly light. Every hour

of every day varies Mary’s presence: circumstances

─

weather, politics,

economics, moods ─

shift and flow. Life

generating sunlight, infinitely inflected with Mary‘s intercessions,

move each and every suppliant. At vespers (evening), approaching the

Western portal, the setting sun animates the judgment day arching the

doorway, anticipating two approaching worlds, the illuminations of

heaven, the shadings of hell. Within, eastward, altar candles anticipate

morning sunrise. At transept, northern exposure offsets temperate South

rose, realizing under the protective wall the temperate garden which

shelters all creatures.

What drives such

activity? Not, presumably, the technical discovery of vaulting, flying

buttresses, illuminated glass. More, the spirit of Mary, a

new influence manifesting new circumstances and desires throughout

Europe in the 12th century.

The Art of Courtly Love

In 1137, Eleanor

succeeded her father William X, as ruler of Aquitane, and married (by

prearrangement of her father) Louis VII of France. She joined Louis on

the second crusade, and exercised considerable influence in arts as well

as politics at Champagne. At Poitiers, she established courtly life and

manners praised by troubadours of the time. Her daughter Marie, Countess

of Champagne, inspired The Art of Courtly Love (Liber de arte honeste

amandi et reprobatione inhonesti amoris), written about 1185 by her

chaplain André. Divorced from Louis in 1152, she married Henry

Plantagenet, 12 years her junior. Her children by both marriages came to

occupy a significant portion of European thrones. Chaucer’s Troilus

and Criseyde assumes the conventions and psychology implicit in the

art

of courtly love.

Capellanus' Art of Courtly

Love

St. Augustine's Revisions

Chaucer's sympathy

for Troilus and Criseyde does not limit his recognition of limitations

attending earthly desires. Pope Innocent focuses our attention on the

costs of seeking satisfaction through the exercise of mortal desires.

Chaucer's counterpart in engaging readers in psychological analysis of

desire, however, is St Augustine. His confessions redirect his desires

to more lasting objects.

Pope Innocent on

Misery

Augustine's Stolen

Fruit

Augustine's Vision

|