Approaching Homer

1

Read together

Reading

sections of the Iliad should prepare you

for more efficient, more

energetic and more productive further reading, and should

inform your participation–

as a listener as well as a speaker–in discussion forums. Each week your approach

to

reading should develop, preparing you also

for your written account of one

passage

for your first

paper. Each week concentrate

on central texts, but also explore readings

in varied media.

Notable characters in the Iliad appeal to

readers and listeners by attempting

Consider

Achilles Curses

Agamemnon

Iliad I, ll 262ff (Fagles p 85)

Odysseus Meets Thersites

Iliad II ll 245ff (Fagles, p 106)

Aphrodite Works

Iliad III ll 146ff (Fagles,

p 132)

Pandarus Strikes

Iliad IV ll 100ff (Fagles, p 148)

Diomedes Wounds Ares

Iliad V ll 998ff (Fagles,

p 192)

Hector Meets Andromache

Iliad VI, 439ff (Fagles, p 208)

Hector Meets Ajax

Iliad VII, V ll 236ff (Fagles, p 221)

Hera & Athena

Face Zeus

Iliad VIII, ll 504ff (Fagles, p 245)

Phoenix Counsels

Achilles

Iliad IX, ll 523ff (Fagles, p 266)

Spies Compete

Iliad X,

ll 523ff (Fagles, p 291)

Sarpedon Seeks

Fame

Iliad XII, ll 337ff (Fagles, p 334)

Hera Seduces Zeus

Iliad XIV, ll 187ff (Fagles, p 374)

Sarpedon’s Last

Stand

Iliad XVI, ll 499ff (Fagles, p 426)

Hector Assumes

Achilles’ Arms

Iliad XVII, ll 159ff (Fagles, p 447)

Hephaestus

Shields Achilles

Iliad XVIII, ll 558ff (Fagles, p 483)

Achilles Goes

Beserk

Iliad XXI, ll 110ff (Fagles, p 523)

Hector Faces

Achilles

Iliad XXII, ll 293ff (Fagles, p 549)

Patroclus’ Final

Appearance

Iliad XXIII, ll 65ff (Fagles, p 561)

Priam Joins

Achilles

XXIV, ll 540ff (Fagles, p 603)

Click for Iliad Passage TOC

2

Approaches to Epic

Following events in Homer's

Iliad offers challenges and presents opportunities. Characters in

the Iliad of course cannot act with full knowledge of

circumstances. Their success, as well as survival, is in training

selective focus on circumstances they presently face, with attention to

shifts in expectations. Consider two features of the Iliad. First,

numerous variations on a common theme occur. Everyone knows the expression

for dying: "bite the dust". But experienced soldiers know that such an end

is the consequence of particular wounds, that myriad other postures mark

memorable endings. Consider the actions of different characters in dying

moments. Patroclus will taunt Hector, forcing upon him the image of

Achilles who will loom above him, a predator far more hateful than Hector

in his present circumstances.

Consider features which characterize Greek

story-telling:

Greek Story-Telling

3

Heroes

Greek heroes survive against great odds to

earn a place in the story, but few survive long, and none find an

afterlife suitable for adventurers beyond the shadowy possibility of

momentary recognition in the memory of storytellers.

Consider the desperate stand of Greeks close

by their ships as Trojans approach their ramparts with blazing torches.

The Greek army faces death by fire with death by drowning close behind.

But consider also the Trojans so near and yet so far from turning the

invaders fated to bring down Troy in flame, presently unable to break

through. Sarpedon, a leading Trojan ally prepares to break through, facing

death from massed Greeks desperate in defense. Sarpedon invites his

younger companion Glaucus to join his heroics, to earn a place in the

story, to live on in memories of future generations. In reminding Glaucus

the costs necessary to validate heroic actins, he steels himself as well

to move towards death:

Sarpedon Seeks Fame

Aristotle offers a Greek

understanding of pride, considering observable qualities in those

recognized as worthy of pride.

Aristotle: Pride

Joan Didion offers a modern appreciation for

those who recognize the costs of actions:

Didion: Morality

Self-Respect

4

Approaching Homer

Read through a book at time without worrying

too much about meaning, but looking for particular scenes you find

memorable. Look for scenes that raise specific questions. Return to a few

of these scenes to consider how events occur in time, with particular

attention to how characters see their changing circumstances. Consider

themes

that will recur in many scenes:

Who is most impressive to fellow soldiers?

What activities get the most respect?

How does conflict arise, and what are the

virtues as well as the costs of conflict?

What is the value of pride, and what costs

attend instances of pride?

How do characters relate to nature in

particular circumstances?

What do characters expect others to approve or

disapprove?

Now consider various particularities of

character, time, place and action.

Appreciating actions through the Iliad

involves your participation in specific settings, particular times and

places, in circumstances which may differ notably from those you find

familiar. Before debating Homeric actions and values consider Homeric

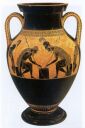

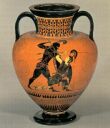

practices. Centaurs, combining the energy of nature with the reflection of

reason, attracted Greeks to the point of obsession. Homeric Greeks

may recognize the dangers of unbridled passion, but they surely found

centaurs captivating as closer to natural forces than mere reasoning man.

Approaching Homer

5

Who's who and what's what

Identification of Greek gods and goddesses may

help. As you trace the interactions of gods and goddesses with particular

mortals, you will come to appreciate their specific powers. Identifying

Athena with wisdom, Aphrodite with love, and Hera with regal power can

focus your attention, but following their activities in specific

circumstances will enable you to discover their personalities. Athena

favors Odysseus, the consummate strategist, and ingenuity rather than

wisdom may better characterize this related goddess and mortal. Aphrodite

favors Paris, and the love she fosters is passion, a passion which

supplants all sense of reason and duty.

Realize that Greek gods and goddesses have

distinctive spheres of influence. Zeus, as the most powerful of them all,

is very different from a monotheistic god. Like an earthly king such as

Agamemnon, many of his associates, not least his wife Hera, test his

authority. He has come to power by overthrowing his own father, and he

fears succumbing to his own offspring. Fate, moreover, not God, determines

the outcome of crucial events. Characters in the Iliad generally act

in credible circumstances. In rare cases gods and goddesses

alter the course of final events by rescuing individuals

from all-but-certain death. In general, however, human events take place

in natural surroundings.

Gods & Goddesses

Identification of Iliad characters may clarify particular scenes.

The Iliad traces the activities of major

fighters. Thersites in Book II offers complaints as a representative of

common foot soldiers, but however important in supporting the great

fighters, common soldiers do not appear as notable, as praiseworthy, as

seekers of fame. You may wish to identify characters appearing in the

Iliad.

Iliad characters

Thomas Bullfinch offers a summary of events preceding and

following the Iliad, as well as those comprising the Iliad. The

Encyclopedia Britannica provides historical background for epic culture.

The Life of Greece provides extended approaches to Greek history and culture. You may find such readings helpful.

Bullfinch on Troy

Britannica Greek History

The Life of Greece

6

Homeric Myth and Epic

Homeric audiences generally would know the

outcome of actions recited by Homer. Homer's success depends not on

suspense, but on the credibility of circumstances, on convincing

characterization, on particularities of time and place which make a

specific action come to life. Actions offer variations on themes. Each

variation traces the various, often unpredictable threads which come

together at a particular moment. Homer’s tapestries characteristically

contrast the expectations of characters with surprises attending shifting

circumstances. A cultivated Greek party-goer centuries more cultivated

than Homeric Greeks, still undergoes age-old transitions: succulent

tastings in good company, rousing melodies, quiescent dreams, but eventual

petrifying nightmares.

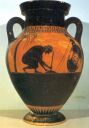

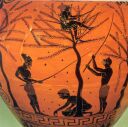

Greek myth also incorporates circumstantial

changes. Consider the story oif Arachne, who gives her name to archnids,

spiders. Her art may serve as a model for appreciating the character

of Homer's stories. Like Helen, Arachne was a skilled weaver, one whose

weavings brought to life the settings and activities of all that live and

the natural and cultural settings in which they move. As her reputation

grew, Arachne had reason to consider herself the greatest of weavers.

Challenging Athena to a competition, Arachne showed not the idealized

depiction of order and power presented by Athena, but the deceits

practiced on mortal girls and women by gods. Athena, outraged, turned her into a

spider, and as a spider she continues to weave today.

On any outdoor dark summer evening a curious

modern observer pressing a flashlight to forehead, shining forward into

grass, will discover innumerable green eyes flashing back, the eyes of

spiders, essential inhabitants of suburban nature.

Homeric epic

presents orally accounts of unfolding of natural desires often at odds

with ideals. The story of is supplants the story of should. Myths offer

condensed stories depicting desires in action. Epic, chanted with lyre, a

simple harp, moved audiences by elaborating on the settings, characters

and activities in which myths play out in historical times and historical

places. For a taste of powerful condensation through myth, consider the

compressed variations developed by Ovid in elegant Latin verse:

Ovid: Arachne

7

Homeric Reading and Writing

Reading

sections of the Iliad should prepare you for more efficient, more

energetic and more productive reading for the next assignment, as well as

preparing you for writing an account of one passage for your first paper.

A successful reading enables you and other readers to reread incidents

fruitfully. Fruitful readings

will develop habits of attention essential for an effective Iliad

paper. Selection of specific Iliad passages focus growing habits of

attention on particular events.

Iliad passages

Readings of passages

The Iliad

a note of thanks for

keeping in touch

a note of thanks for

keeping in touch